Read updates on hurricane Milton

- October 17, 2024 – Milton: insured wind and flood loss estimate

- October 10, 2024 – Milton: fifth U.S. landfalling hurricane devastates Florida

- October 9, 2024 – Milton to make landfall as major hurricane on Florida’s West Coast

- October 8, 2024 – After rapid intensification, Milton turns towards Tampa Bay

- October 7, 2024 – Hurricane Milton forms, following Helene

Update: October 17, 2024

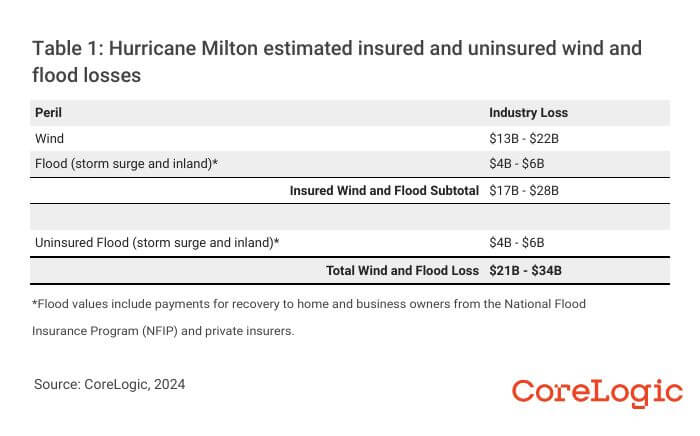

Cotality Hazard HQ Command Central™ estimates that insured wind and flood losses from Hurricane Milton will be between $17 billion and $28 billion. The total amount of damage, including losses to uninsured property, will be between $21 billion and $34 billion (Table 1).

These losses include damage to buildings, contents, and business interruption for onshore residential, commercial, and industrial property. This estimate does not include damage to offshore property, such as inland marine, ocean-going marine cargo and hull, and personal boats. The estimate also does not include damage to local or federal government buildings or infrastructure (e.g., roads, bridges).

The flood losses include damage from both storm surge and precipitation-induced inland flooding. Insured flood losses include those covered by the private flood insurance markets and the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

The losses do not explicitly include damage from the tornado outbreak.

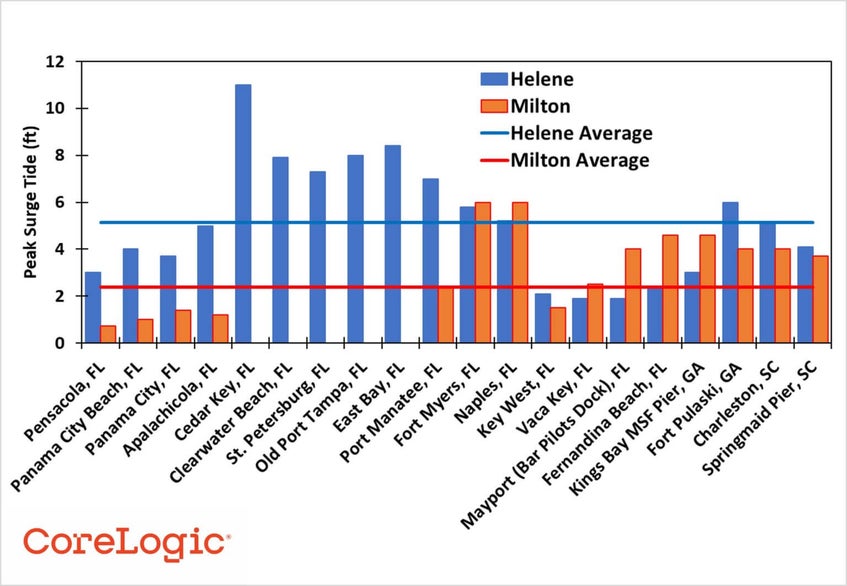

An assessment of the Hurricane Milton damage in Florida indicates that the majority of losses will be from wind and will account for the bulk of the privately insured losses. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) tidal gauges indicate that the most extreme coastal flood losses in Florida are in Sarasota and areas to the south such as Naples and Ft. Meyers.

Precipitation-induced inland flood losses are expected to be primarily in the Tampa Bay area. Severe storm surge or precipitation-induced flooding should impact a lower number of properties compared to the number affected by wind. Despite the high uptake of NFIP policies along the Florida coast and inland areas, relative to the national average take-up rates, the combined flood losses will account for a small proportion of the insured loss total.

Wind speed and precipitation depth measurements taken during Hurricane Milton’s landfall presented a unique scenario. Milton’s interaction with a cold front to the north combined with heavy wind shear at the time of landfall, while the storm underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, meant that the strongest winds and most severe inland flooding did not present in a standard, symmetrical distribution around the eye.

The shear and interaction with the cold font meant that the strongest winds and heaviest precipitation fell on the opposite side of landfall over the greater Tampa Bay area. To add to the complexity, weather gauges in coastal Florida also measured hurricane force winds over Sarasota, south of where Milton made landfall.

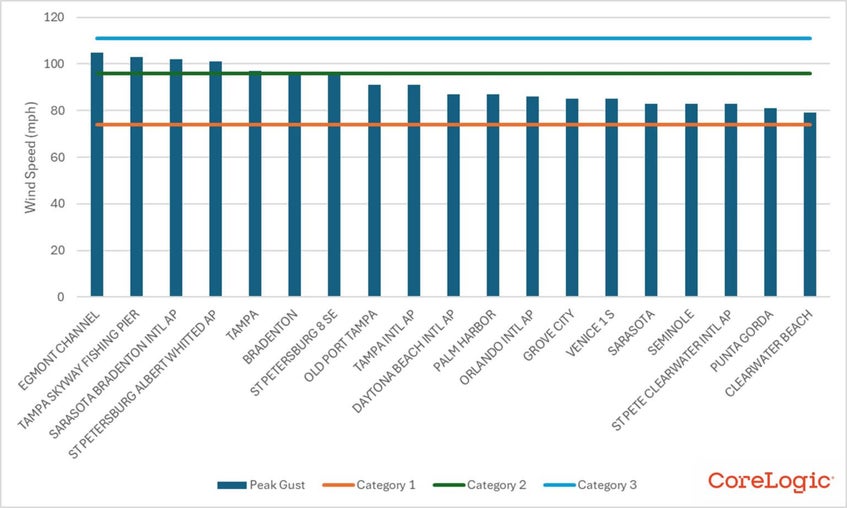

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) reported peak wind gusts of Category 1 to 2 strength, reaching between 80 and 100 mph around the Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg areas. The strongest gust was 105 mph at the mouth of Tampa Bay. A weather station at the Tampa Bay International Airport reported a maximum gust of 91 mph.

As Milton crossed the Florida Peninsula, weather stations recorded peak gusts of 72 mph at the Orlando Executive Airport. On the east coast of the state, a weather station at the Daytona Beach International Airport recorded a peak gust of 87 mph. (Figure 1).

Damage from peak gusts of these magnitudes indicates damage to older or more vulnerable structures like manufactured homes, but not necessarily to widespread structural damage.

The Cotality Hazard HQ Command Central event response team traveled to Central Florida to inspect the level and type of damage along both the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts, as well as across the peninsula. Given the large concentration of property in the Tampa Bay area, including older residential and high-value commercial structures (e.g., hotels), large insured losses were possible but needed validation.

The reconnaissance work is ongoing but preliminary reports from the team did not note widespread structural damage, especially in the population centers of the Tampa Bay area, which aligns with aerial imagery analysis. The number of roofs with tarps and sites with severe wind damage were on par with the level of damage caused by Category 1 winds. There were occasional homes with roof damage and downed tree limbs that could lead to claims, but there were also examples of even older homes that were completely intact.

In other parts of Florida like Orlando, the team observed damaged business signs and downed tree limbs, but little to indicate substantial, widespread structural damage.

The most severe storm surge flooding occurred to the south of the landfall location at Siesta Key, Florida. Flood depths greater than 6 feet above the ground surface were reported as far south as Ft. Meyers. The event response reconnaissance team visited Manasota Key, just north of Boca Grande. The team reported widespread storm surge damage, but the number of structures on the island is low; there are only 1,800 residents and approximately 900 households, according to Census Reporter and U.S. Census Bureau.

Fortunately, little storm surge flood damage occurred around Tampa Bay. Much of the damage noted by the team was caused by Hurricane Helene two weeks prior. The primary wind direction during Hurricane Milton was offshore, pushing water away from downtown Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg.

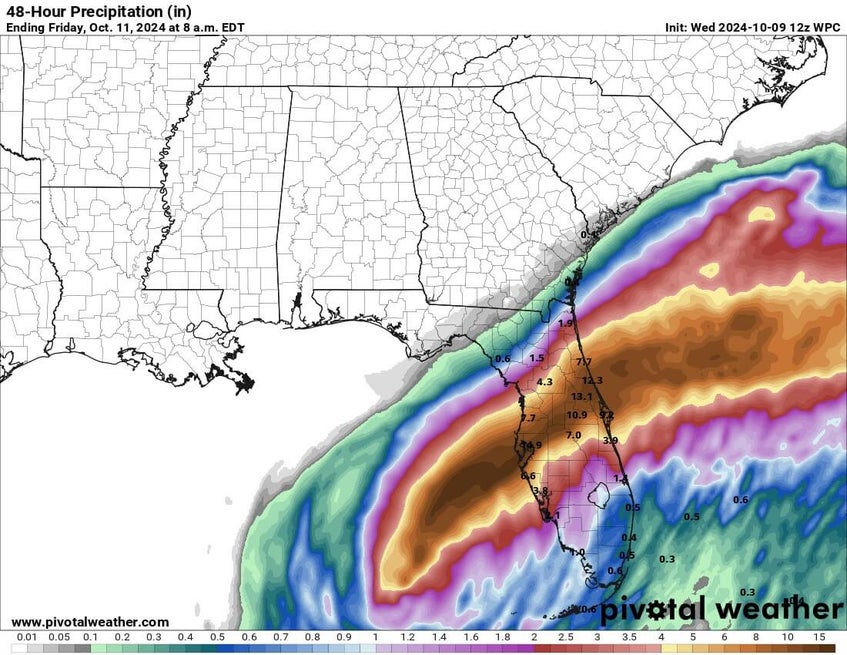

Precipitation gauges across the state recorded a maximum rainfall depth of approximately 19 inches in the Tampa Bay area. Stations across Central Florida recorded rainfall depths between 10 and 15 inches.

The challenge of back-to-back storms

Two major hurricanes making landfall in Florida in under two weeks will make for a challenging recovery for the residents of Florida and the companies that insure the buildings in which they reside.

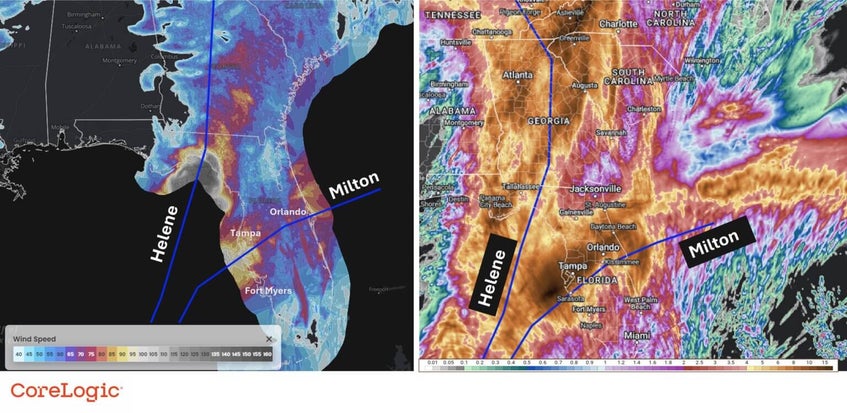

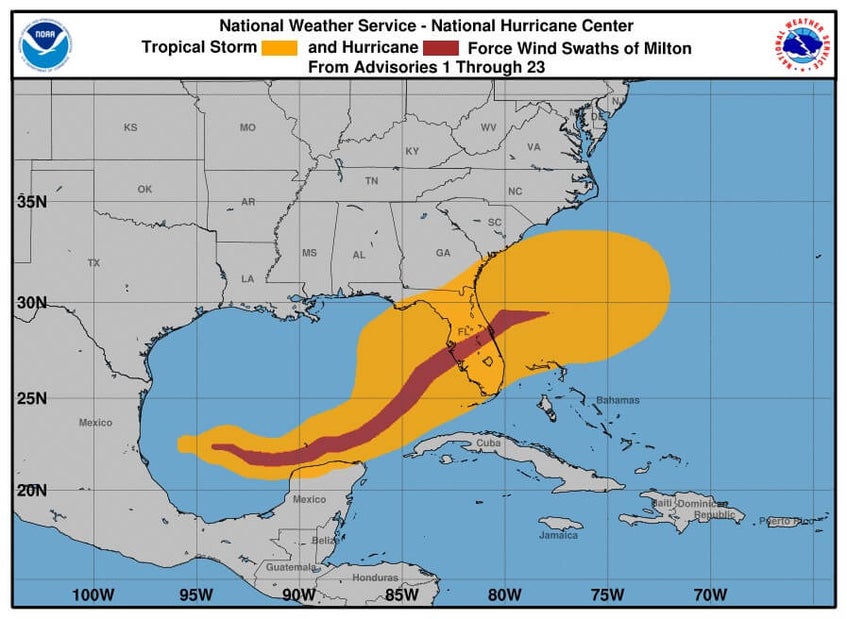

While Hurricane Helene made landfall over the Big Bend region of Florida, miles from Tampa Bay, there is overlap between the tropical storm force wind fields, storm surge, and precipitation (Figure 2) leading to difficult loss attribution between the two storms.

The overlap of severe storm surge damage in the Tampa Bay area during Hurricane Helene and potential wind damage during Hurricane Milton creates a scenario where losses from flood and wind damage may be more difficult than normal to differentiate.

Two major hurricane landfalls in rapid succession will create an elevated demand for materials and labor to repair and restore.

Hurricane Helene’s landfall two weeks prior to Milton and its widespread impact from Florida to Virginia put an enormous strain on the finite number of available resources. Many professionals capable and licensed to restore flood-damaged property are committed to other regions. The increased demand in Florida for professional services and rebuilding materials may inflate claim magnitudes beyond what would traditionally occur if Milton made landfall without prior events.

Future hurricane Milton updates

Cotality Hazard HQ Command Central is continuing to review the damage Hurricane Milton caused in Florida. At this point, no additional industry loss estimates are expected unless new data becomes available.

Update: October 10, 2024

In a flash, Hurricane Milton came and went. As of Thursday, Oct. 10, it had been five days since the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began issuing advisories on Tropical Storm Milton. Since then, Milton organized and strengthened. The rate at which Hurricane Milton strengthened was astounding.

At 2 p.m. EDT on Sunday, Oct. 6, Milton began to strengthen from a tropical storm into a hurricane, with maximum sustained winds surpassing 74 mph. Within 24 hours, at 2 p.m. Monday, Oct. 7, Milton’s maximum sustained winds increased an additional 95 mph. This rate of intensification is more than double the requirement for rapid intensification. Milton was only outdone by infamous historical hurricanes like Wilma in 2005 and Felix in 2007.

Maximum sustained winds peaked at 180 mph on Monday afternoon (a strong Category 5) and the hurricane’s pressure hit a minimum of 897 mb. At this point, Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg were at the center of the NHC cone of uncertainty. A major hurricane making landfall in a large population center would be the worst-case scenario. The uncertainty in the exact landfall location made early loss estimation incredibly difficult.

A landfall directly over Tampa Bay, or just to the north, would have brought severe winds to an aging building stock and extreme levels of storm surge, as the southern edge of a hurricane – which is typically the strongest – would be blowing directly ashore.

Fortunately for the residents of Tampa Bay and the insurance industry, Hurricane Milton wobbled on its path, keeping a much more southerly track than models originally anticipated. In the last 12 hours before landfall, Milton ran into an area of increased vertical wind shear, lowering the intensity of the storm just before landfall.

According to the NHC, Milton made landfall as a Category 3 storm just south of Tampa near Siesta Key around 8:30 p.m. EDT, with estimated wind speeds over 120 mph. The more southern track meant that storm surge flooding in Tampa Bay was virtually non-existent. Instead, tidal gauges indicated over 8-foot storm surge in Sarasota and in Naples and up to 6 feet in Fort Myers.

The Tampa Bay area experienced less storm surge than expected due to a phenomenon called reverse storm surge, which is when hurricane winds blow east to west to push water away from the coastline

As the storm moved overnight across central Florida, it brought significant flooding and destructive winds, leaving nearly 3.4 million people without electricity.

Wind gauges across the peninsula recorded maximum wind gust of 105 mph in Egmont Channel. Stations in Sarasota, St. Petersburg, Venice, Tampa, and Venice recorded similar speeds. Hurricane Milton left a relatively narrow band of hurricane-force winds as it crossed the peninsula (Figure 1), though much of the state felt tropical storm force winds.

If this was the entire story of Hurricane Milton, estimating the industry insured losses would be simpler. But there is another complicating factor to consider.

As Milton approached Florida, it began to interact with the jet stream over the southeastern U.S. This interaction created a situation where the winds on the northern and northwestern sides of the hurricane, those blowing east to west, and generally known to be weaker, were much stronger than those of a typical hurricane. As the forecasted landfall location moved further south, the expected wind impacts in Tampa Bay decreased. But this was not the case.

Milton’s unique wind profile, with stronger winds blowing on the northern and northwestern side of the eye, is likely to contribute significantly to the final industry insured loss estimate.

Although the worst-case scenario of a direct landfall in Tampa did not occur, wind and storm surge losses across the state, including on the East Coast, will be material.

Future hurricane Milton updates

Cotality Hazard HQ Command Central™ is currently working to find appropriate proxy events from the North Atlantic Hurricane Model that will adequately approximate wind and storm surge losses in Florida. Post-landfall proxy events and an initial industry insured loss estimate will be available on Friday, Oct. 11.

Update: October 9, 2024

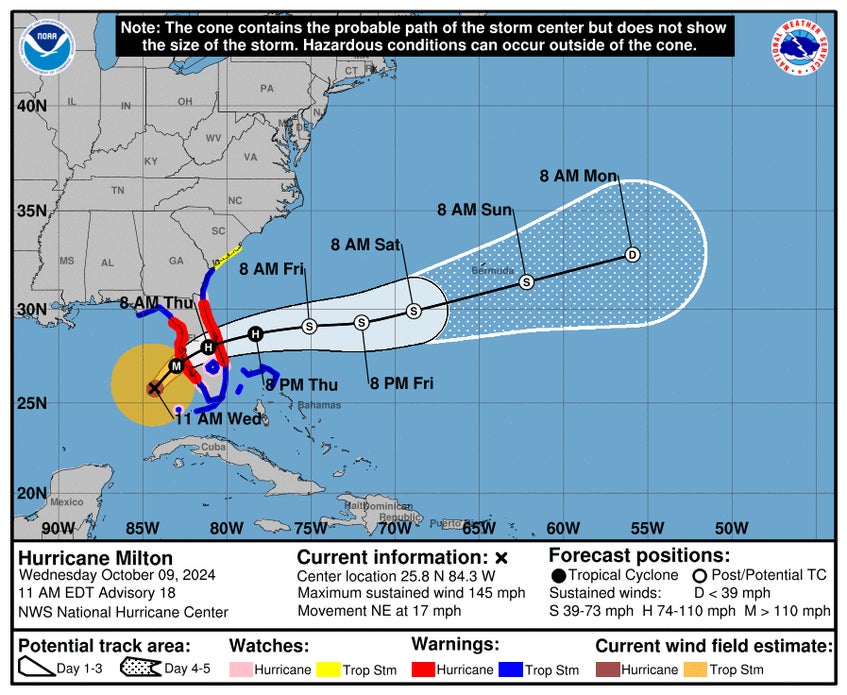

Hurricane Milton is expected to travel through the eastern Gulf of Mexico today. It will make landfall on Florida’s west-central coast on Wednesday evening and then exit over the Atlantic Ocean from the state’s east coast on Thursday.

The storm currently has maximum sustained winds of around 145 mph (230 km/h). As a current Category 4 storm, Milton is expected to remain a highly dangerous major hurricane when it reaches the coast; it will maintain hurricane strength as it crosses the Florida peninsula through Thursday. As the storm moves eastward into the Atlantic, gradual weakening is anticipated.

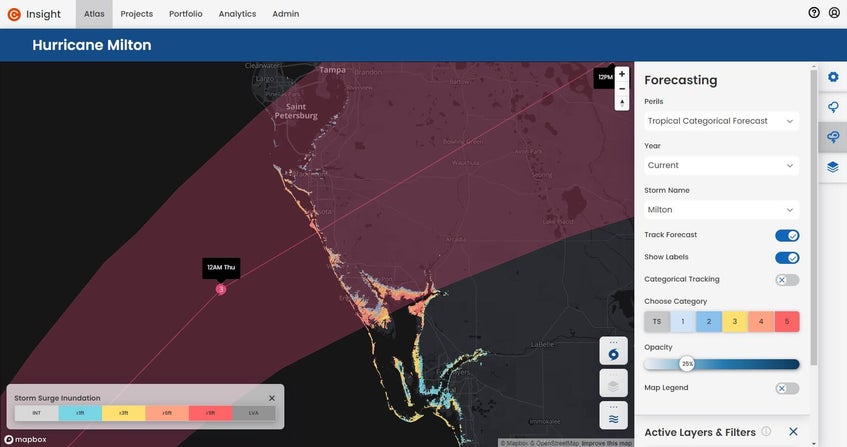

Storm surge is expected to be very high along the Florida coastline. The highest water levels are expected along the immediate coastline near and just south of the landfall area where the storm surge will combine with large, hazardous waves. Storm surge could be up to 12 feet in Tampa Bay and up to 15 feet between Anna Maria Island and Boca Grande.

Rainfall totals of 6 to 12 inches are anticipated across central and northern parts of the Florida Peninsula through Thursday, with some areas potentially receiving up to 18 inches. This heavy rainfall poses a significant risk of catastrophic, life-threatening flash floods and urban flooding, as well as moderate to major river flooding.

Future hurricane Milton updates

Cotality Hazard HQ Command Central™ will continue to watch Hurricane Milton. Post-landfall proxy events and initial modeled insured wind and storm surge losses will be available later this week.

Update: October 8, 2024

In the span of just 10 hours, Hurricane Milton broke the scales, strengthening from a Category 1 hurricane to a Category 5 hurricane.

This intensification pattern is reminiscent of Hurricane Beryl, which quickly intensified into a dangerous — and unprecedented — Category 5 storm early this season.

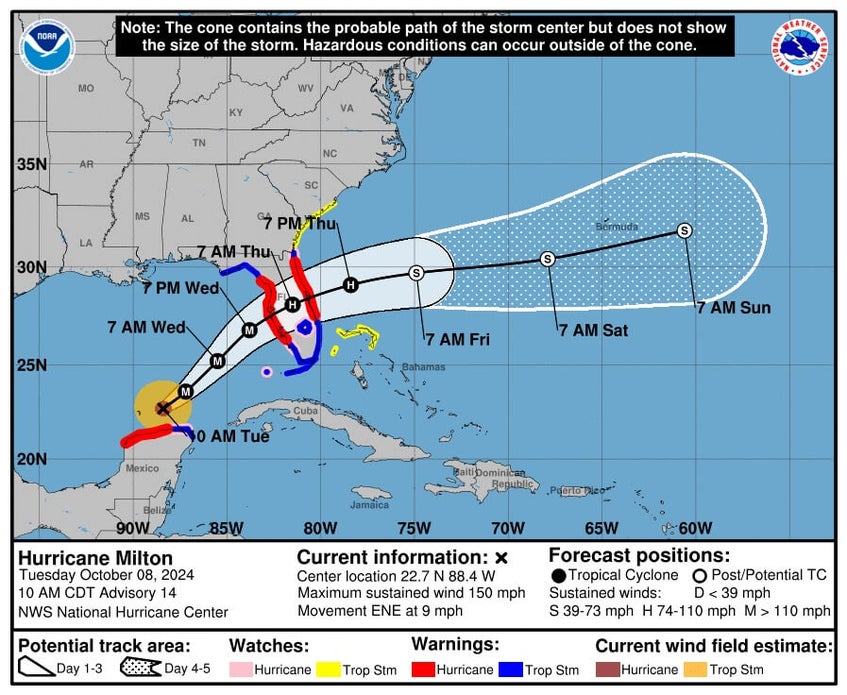

As of 10 a.m. CDT on Tuesday, Oct. 8, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecast shows that Hurricane Milton is just north of the Yucatan Peninsula with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph.

In the next few hours, Milton will turn towards the northeast with Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg at the center of the cone of uncertainty (Figure 1).

Milton’s intensity will fluctuate over the next 24 hours as the storm undergoes an eyewall replacement cycle. While the intensity may drop temporarily during this period, the storm will grow in size. This transformation will increase the amount of coastline exposed to storm surge flooding.

Hurricane Milton will enter hostile environmental conditions during the last 12 hours of its pre-landfall life, when dry air entrapment and vertical wind shear increase. To what degree this will decrease the storm’s intensity is still uncertain. Currently, Hurricane Milton forecasts indicate a direct landfall over Tampa Bay as a Category 3 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 125 mph.

It is important to note that very small changes in the exact landfall location will have monumental impacts on the financial impact of the storm. A direct landfall, or one just north of Tampa Bay, would be a worst-case scenario because the winds and storm surge flooding may impact a greater number of properties. A more southern landfall would reduce the impact in Tampa Bay but devastate Florida communities along the coast near Sarasota.

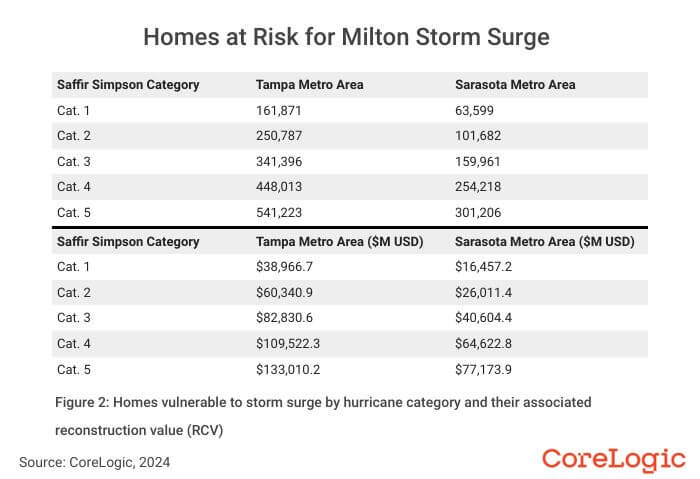

500,000 homes at risk of storm surge flooding

Cotality estimated that as many as 500,000 residential properties in the Tampa Bay and Sarasota metro areas are at risk of storm surge flooding from Hurricane Milton. These homes have a combined reconstruction cost value (RCV) of $123 billion.

This estimate assumes that Hurricane Milton will be Category 3 strength at landfall. There remains uncertainty on the exact landfall intensity.

The strength and size of the hurricane at landfall will make a significant difference in the number of properties at risk. If Milton makes landfall as a weaker Category 1 hurricane, as many as 225,000 homes with a combined RCV of $55 billion could be at risk.

However, if Milton does not weaken substantially prior to landfall and makes landfall as a Category 4 hurricane, as many as 700,000 homes with a combined RCV of $174 billion could be at risk.

Future hurricane Milton updates

Cotality Hazard HQ Command Central™ will continue to watch Hurricane Milton. If there is significant change to the 10 a.m. CDT forecast released on Wednesday, Oct. 8, an update will be available.

Otherwise, post-landfall proxy events and initial modeled insured wind and storm surge losses will be available later this week.

Update: October 7, 2024

Just days after Hurricane Helene made landfall in the Big Bend region of the Florida Gulf Coast and subsequently flooded much of the southeastern U.S., another tropical system formed and is heading for the States.

On Sunday, Oct. 5, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began issuing advisories for Tropical Storm Milton. Milton strengthened to a hurricane on Oct. 6 before becoming a major hurricane on Oct. 7 over the Gulf of Mexico’s warm sea surface temperatures.

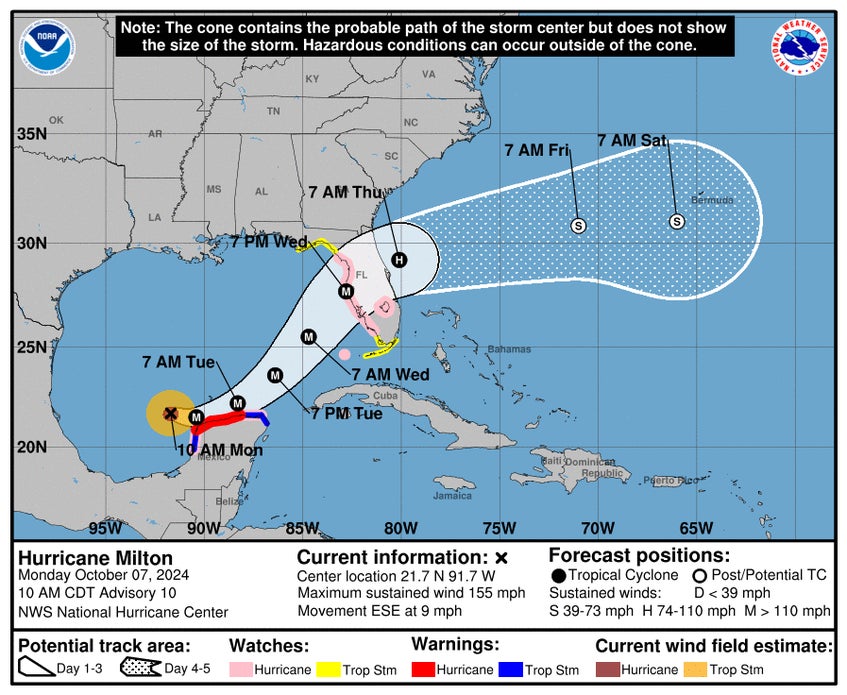

The NHC 11 a.m. EDT forecast on Monday, Oct. 7 shows that Milton will travel east-southeast across the southern Gulf of Mexico before speeding up and turning east-northeast, with Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg in its path (Figure 1).

Hurricane Milton followed a track further to the south than originally anticipated, and interactions with the Yucatan Peninsula could still affect the storm. A more southerly track also has ramifications for the eventual Florida landfall location.

Risk Quantification and Engineering (RQE®) and Navigate™ model users can download pre-landfall hazard-based proxy events from the Client Resource Center (CRC).

There should be very little dry air or vertical wind shear to hamper development as Milton begins to turn east-northeast. For the next 24 hours, Hurricane Milton will continue to strengthen. Starting about 24 hours before landfall, Milton will enter an area of less favorable conditions, which could weaken the storm before landfall. However, there remains a lot of uncertainty regarding how much weakening will occur.

As of 11 a.m. EDT on Monday, Oct. 7, the NHC forecast shows Milton making landfall with maximum sustained winds of 126 mph. This would make Hurricane Milton a Category 3 tropical cyclone.

There is still uncertainty in the exact landfall location and intensity. However, a major hurricane landfall in a populated region of Florida like Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg could become one of the most damaging storms in recent years.

The potential for extreme winds and devastating storm surge is high, especially given the shape of Tampa Bay and the shallow waters off the coast, both of which could exacerbate coastal flooding.

A landfall north of Tampa Bay would be the worst-case scenario from a storm surge flooding perspective, as the onshore winds on the southeastern side of the hurricane would be flowing right into the bay. If Hurricane Milton makes landfall further south, storm surge flooding might be less in Tampa Bay, but it would be a significant hazard in Sarasota, Punta Gorda, or Ft. Meyers.

1921: a historical precedent for hurricane Milton

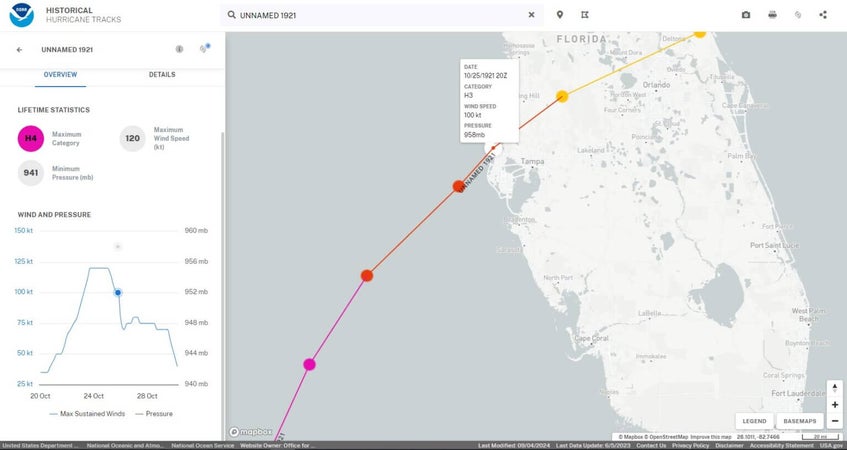

The last hurricane to directly hit the Tampa Bay area was over 100 years ago.

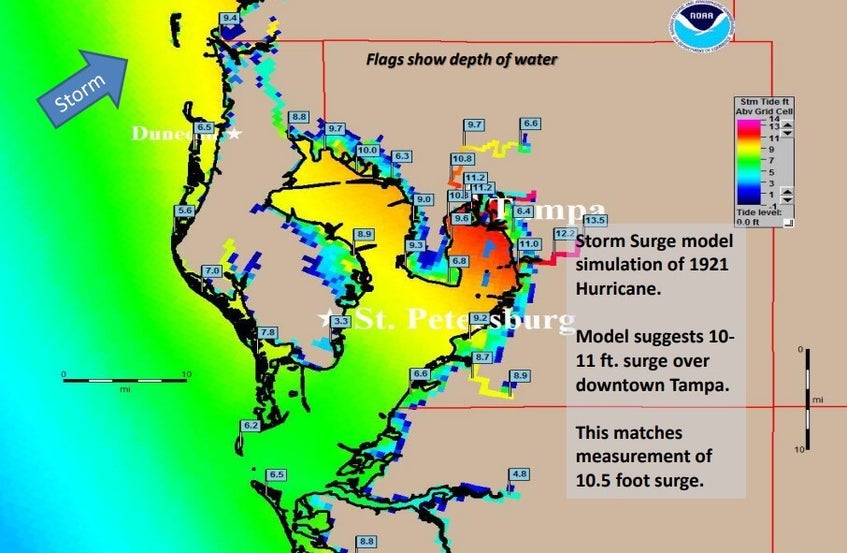

The 1921 Hurricane, also known as the Tarpon Springs Hurricane, struck Florida just north of Tampa Bay in late October 1921. The storm made landfall in Tarpon Springs (Figure 2) on Oct. 25 as a Category 3 storm with sustained winds of around 115 mph. It caused significant destruction.

The storm generated a surge up to 11 feet in Tampa Bay (Figure 3), inundating coastal areas and causing extensive flooding. The property damage in Tarpon Springs and surrounding areas was severe, with homes, businesses, and infrastructure heavily affected.

The estimated cost of the damage was approximately $10 million at the time, which would be significantly higher today when adjusted for inflation.

More significant than inflation is the exposure growth in the area. Since 1921, Tampa Bay, St. Petersburg, and the surrounding cities have grown significantly.

Currently, the Tampa Bay-St. Petersburg area has a diverse array of buildings, ranging from historic landmarks to modern skyscrapers. This region, which includes the cities of Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Clearwater, as well as surrounding municipalities, reflects significant urban development over the past decades.

Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg have a mix of residential buildings, ranging from single-family homes to high-rise condominiums. In the city of Tampa alone, there are approximately 157,000 housing units. St. Petersburg adds around 109,000 housing units to the total. When considering the broader Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, Florida metropolitan area, including other parts of Hillsborough, Pinellas, and Pasco counties, the number of residential buildings increases to 1.5 million.

The commercial real estate sector in the Tampa Bay area comprises numerous office buildings, retail spaces, hotels, and industrial properties. In Tampa, notable commercial districts such as downtown, Westshore, and Ybor City contribute to a dense concentration of commercial buildings. St. Petersburg’s downtown and waterfront areas are similarly rich in commercial properties, including several notable office towers and retail centers.

.jpg)